Start improving with Life QI today

Full access to all Life QI features and a support team excited to help you. Quality improvement has never been easier.

Organisation already using Life QI?

Sign-up

Published on 22 December 2022 at 08:47

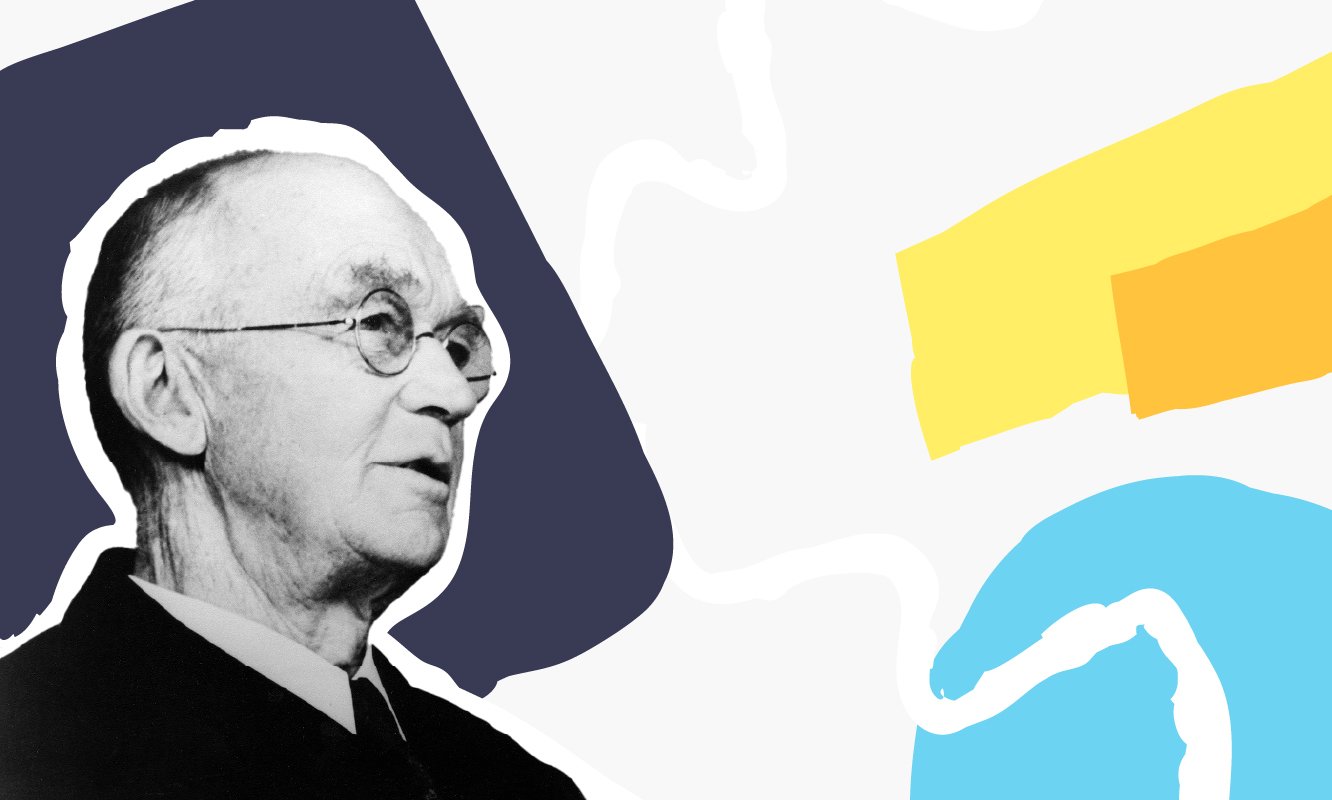

Born in Massachusetts in 1869, Ernest Codman is known as the ‘Father of Outcome Management’. He worked as a clinician and still influences Quality Improvement (QI) to this day. Ernest Codman trained as a surgeon and made it his lifelong work to follow up on his patients after their treatment and systematically record their outcomes.

He was way ahead of his time a pioneer in safety science and QI, studying and analysing the outcomes of surgical care in the pursuit of excellent quality and patient outcomes.

Whereas most of the quality heroes we’ve been exploring in this series of articles worked in the manufacturing and process industries, Codman developed quality theories specifically for healthcare while working as a surgeon, carrying out ground-breaking work in healthcare way ahead of his time.

Acknowledged by many as the ‘founder of outcomes-based patient care’, he believed that such information on patient outcomes should be made public in order to guide patient choice.

Let’s find out more about his background and influences. Let's see what drove him to become such a pioneer in the field of quality in healthcare.

Ernest Amory Codman MD was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1869. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1895, going on to work at Massachusetts General from 1902 to 1914.

Codman was a pioneer in many areas throughout his career. He became interested in the newly discovered x-rays in 1895 and became a radiologist at the Boston Children’s Hospital in 1899. While a junior surgeon at Massachusetts General, he became interested in the shoulder, and published many papers on the subject. Indeed, even today, we remember him in phrases such as ‘Codman’s test’ and Codman’s exercises, in relation to shoulder operations and post shoulder operation care.

His pioneering work as a surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital was ground breaking at the time. He made it his mission to follow up on his patients after their treatment and systematically record their outcomes. He noted errors and linked these to outcomes to ensure they did not happen again.

However, when he shared his pioneering work of collecting outcomes data, it did not make him popular with his peers and ruffled many feathers.

In 1911 Codman left the Massachusetts General Hospital to set up his small hospital, known as the ‘End Results Hospital’. He started to collect patients’ outcome data, analysed it, shared it with patients and started to publish his results. We’ll find out more about the hospital later on in the article.

Codman also became interested in bone sarcoma and in 1920 he set up the first national registry for bone sarcoma. Codman was also a co-founder of the American College of Surgeons and helped set up its Hospital Standardisation programme. Ernest Codman died in 1940, leaving behind a legacy in healthcare that is still relevant today.

In the Institute for Innovation and Improvement's 2008 report 'Quality Improvement: theory and practice in healthcare' the authors identify the following: ‘The history of clinical quality improvement goes back to conceptualisations of clinical work as craft, with individuals responsible for the quality of the outcome, and as early as 1916 Codman focused on the End Results System of auditing clinical care.’

Codman came up with the concept of his 'End results system' while he was working at Massachusetts General Hospital. He went on to develop it more fully when he left to start up his own hospital in 1911. The main focus of his new hospital was the evaluation of care and sharing results of patient care. This practice was the forerunner of what we would call today: evidence-based medicine.

The premise of the ‘End results system’ as summed up by Codman himself is the following. “The common-sense notion that every hospital should follow every patient it treats, long enough to determine whether or not the treatment has been successful, and then to inquire, ‘If not, why not?’ with a view to preventing similar failures in the future.”

The truth in this concept is recognised today as ‘best practice’ and what should be done. ‘Now, Codman's idea is accepted dogma. We recognize that patients' outcomes often fall short of our collective expectations. One important reason for this failure is that scientific evidence about patient care (including diagnosis and management) is unevenly and inconsistently applied. This phenomenon is known as the evidence-to-practice performance gap.’

Codman's End results system involved collecting patient data on cards and following and analysing the results. He proposed every surgeon's results should be available to access both by other surgeons and the public. The essence of this was to propose that hospitals could be recognised for their quality of care - or lack thereof.

Described as: ‘an early pioneer of the study of outcomes and the integration of those data into the quality care of the patient,' when Codman discharged patients from his hospital he recorded errors and measured end results, grouping errors by type – such as lack of care, lack of skill etc.

Codman recognised the fact that: ‘..rarely were the results of a single surgeon significantly better than that surgeon’s colleagues’ results’ and went on to propose his End Results system to peers at a meeting at Boston Medical Library in 1915, including with it an uncomplimentary cartoon commenting on his peers’ practices. The proposal was rejected as Codman’s peers feared what would happen if their outcomes were published.

Dr. Codman said: ‘You hospital superintendents are too easy. You work hard and faithfully reducing your expenses here and there-a half—cent per pound on potatoes or floor polish. And you let the members of the [medical] staff throw away money by producing waste products in the form of unnecessary deaths, ill-judged operations and careless diagnoses, not to mention pseudo-scientific professional advertisements.’

Codman's published 'A Study in Hospital Efficiency' in which he published results of his own practice. They showed that of the 337 patients discharged, Codman recorded 123 errors.

To summarise Codman’s influence – and disappointing lack of acknowledgement during his lifetime - in the publication 'Clinical Audit: a Manual for lay members of the Clinical Audit Team’ the report states:

‘Codman was recognised as the first true medical auditor following his work in 1912 on monitoring surgical outcomes.Although his work is often neglected in the history of healthcare assessment, Codman’s work anticipated contemporary approaches to quality monitoring and assurance, establishing accountability and allocating and managing resources efficiently.

Whilst Codman’s clinical approach is in contrast with Nightingales more epidemiological audits, these two methods serve to highlight the different methodologies that can be used in the process of improvements to patient care.’

Codman was a pioneer in quality in healthcare, with a focus on the patient’s outcomes, years ahead of his time.

“Every hospital should follow every patient it treats, long enough to determine whether or not the treatment has been successful, and then to inquire 'if not, why not' with a view to preventing similar failure.”

- Ernest Codman

Full access to all Life QI features and a support team excited to help you. Quality improvement has never been easier.

Organisation already using Life QI?

Sign-up